Taino Culture

- ninedivinecreation

- Sep 20

- 15 min read

Updated: Sep 24

Taíno culture was rich, diverse, and deeply connected to the natural world around them. It’s a fascinating blend of social organization, spirituality, art, and daily life. Here’s a deeper dive into various aspects of Taíno culture:

1. Social Organization and Leadership

Taíno society was hierarchical, but it also had a sense of communal responsibility. It was organized into chiefdoms called cacicazgos, each led by a cacic (chief). The cacique had significant authority but was also expected to be a protector and provider for his people.

Cacique: The chief, often a figure of both political and spiritual power, was responsible for making important decisions, overseeing trade, and maintaining order. They were usually the head of a large extended family and were often chosen through hereditary lines.

Naborias: These were common people, often farmers, fishermen, or warriors. They lived in the bohíos and played vital roles in the economy of the society.

Bohechíos: These were the larger ceremonial houses, where rituals and meetings were held.

Nitainos: The nobility, or elites, who assisted the caciques in governance.

Taíno society was matrilineal, meaning that lineage and inheritance passed through the mother’s side. This is an important distinction because in many other societies of the time, inheritance passed through the father. It reflected the importance of women in their social structures.

2. Spirituality and Religion

Religion was central to Taíno life, and they believed in a spiritual world that was intertwined with the natural world. Their deities were tied to nature, and their rituals reflected a deep respect for the elements and the forces of the universe.

Zemí: The Taíno believed in spirits called zemí, which were the manifestations of gods and ancestors. These spirits were thought to inhabit the natural world—trees, rocks, animals, and even the sky. The Taíno created zemí figures, often carved from wood or stone, which they would worship and offer gifts to.

Bohio and Areyto: The bohío (the traditional Taíno house) often served as a place for religious ceremonies. The areyto was a sacred dance or ceremony that could be used to honor the gods, mark important events, or tell stories of Taíno history and cosmology.

Yucahú: One of the central deities in Taíno belief, Yucahú was the spirit of the sea and the creator god. He was responsible for providing food, especially the yam and cassava crops.

Atabey: The mother goddess, symbolizing fertility and the earth. She was also a protector of the people and their crops.

The Taíno also believed in an afterlife. They thought that the souls of the dead would go to a peaceful, idealized world. The dead would be guided by the spirits of the ancestors, ensuring they had a good life in the afterlife.

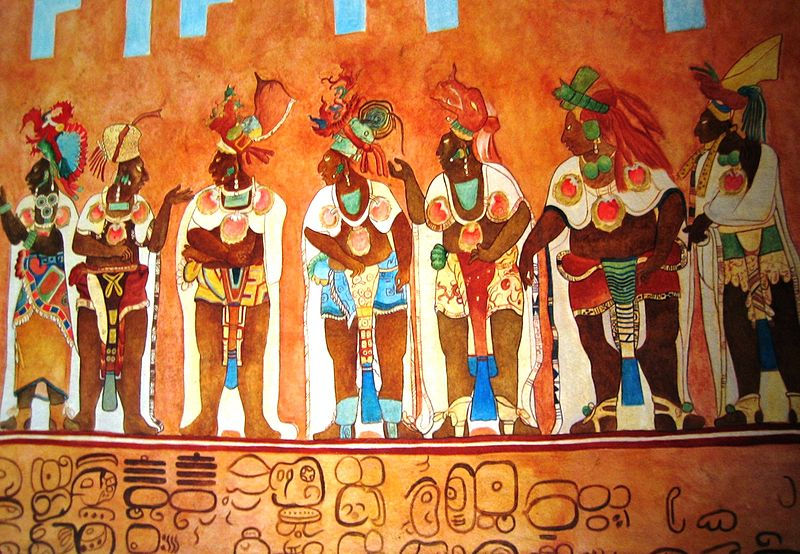

3. Art and Symbolism

The Taíno had an incredibly rich artistic tradition, deeply tied to their religious beliefs and daily life.

Petroglyphs: The Taíno created elaborate petroglyphs (rock carvings) that often depicted animals, spirits, and symbols of importance. These carvings can be found across the Caribbean, particularly in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

Pottery: The Taíno were skilled potters, creating beautifully decorated ceramic vessels for both practical and ceremonial uses. Many of these pots were used to store food, but others were created for rituals.

Zemí Figures: These small, carved idols represented the spirits (zemí). They were made from wood, bone, and stone, and they often depicted human, animal, or abstract forms. Some were used as offerings to the gods during religious ceremonies.

Body Art: Taíno people also adorned their bodies with tattoos, often made from natural pigments like red, black, and yellow. These tattoos were symbolic and could reflect a person’s status, achievements, or spiritual beliefs.

4. Economy and Agriculture

The Taíno were primarily agriculturalists, relying heavily on their crops for sustenance. They had a deep understanding of their environment, and their farming practices were highly sophisticated.

Cassava (Manioc): The most important crop in the Taíno diet was cassava, a root vegetable rich in starch. They processed it into bread called cassava bread or arepa. This was often served with fish or other foods.

Fishing: The Taíno were skilled fishermen, using nets, traps, and even poisoned bait to catch fish. They also used dugout canoes to travel and fish in coastal waters.

Hunting and Gathering: In addition to farming, the Taíno hunted small animals like iguanas, hutia (a rodent), and birds. They also gathered fruits, nuts, and other plant-based foods from the forests.

5. Language

The Taíno spoke a language belonging to the Arawakan language family, known as Taíno. While the language is not widely spoken today, many Taíno words have survived in modern languages, especially in Caribbean Spanish. Words like canoa (canoe), hurricane (from juracán), tobacco (from tabaco), and barbacoa (barbecue) all come from Taíno.

6. Architecture and Housing

The Taíno built homes that reflected both practical needs and spiritual beliefs.

Bohíos: The typical home for the common people was the bohío, a small, round, thatched structure made from wood and palm leaves. It provided shelter from the elements and was designed to allow airflow in the hot Caribbean climate.

Caney: The caney was a larger, rectangular structure used for ceremonies and meetings. It often housed the cacique and his family.

7. The Role of Women

Women in Taíno society played an important role in both domestic life and the economy. As the matrilineal society placed importance on lineage through the mother, women were responsible for the cultivation of crops like cassava, the preparation of food, and the management of family life. Some women held positions of leadership as well, and it was not uncommon for women to be highly respected within the community.

8. Technology and Tools

The Taíno developed various tools and technologies from the natural materials available to them, including wood, stone, and bone.

Stone tools: They used stone tools for hunting, fishing, and food preparation. Their weapons included machetes, spear tips, and axes made of sharpened stone.

Dugout Canoes: One of their most significant technological achievements was the creation of dugout canoes, made by hollowing out large tree trunks. These were essential for fishing, trade, and transportation across the islands.

Tobacco: The Taíno were among the first to cultivate tobacco. They used it in their religious rituals and also for medicinal purposes.

9. The Taíno Encounter with the Spanish

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 marked the beginning of profound changes in Taíno culture. Initially, the Taíno were hospitable, but the Spanish quickly sought to exploit their land, labor, and resources. The introduction of European diseases and the harsh encomienda system led to the rapid decline of the Taíno population.

Despite this, many aspects of Taíno culture survived in the Caribbean, both through the fusion with African and European traditions and in the persistence of Taíno-descended communities. Today, their cultural legacy can still be seen in Caribbean folklore, language, cuisine, and art.

Taíno ceremonies were deeply intertwined with their spiritual beliefs, connecting them to the natural world, their ancestors, and the forces of the universe. The ceremonies often involved communal participation, as they were designed to maintain harmony between humans and the spirits (zemis) and to ensure prosperity in the community. Below are some key aspects of Taíno ceremonies:

1. Religious Context of Taíno Ceremonies

The Taínos were polytheistic, worshipping a pantheon of gods and spirits known as zemis. The zemis were believed to inhabit natural objects like stones, trees, and sacred idols, and were associated with the elements of nature (earth, water, fire, air). They also revered their ancestors as spiritual guides.

Key zemi figures included:

Yúcahu: The god of cassava, maize, and the sea, often considered the most important deity.

Atabey: The goddess of fertility and the moon, considered the mother of all life.

Juracán: The god of hurricanes, winds, and storms.

Behike: The zemi of healing and medicine, represented through the priestly figure of the bohíque.

2. Types of Taíno Ceremonies

Most Taíno ceremonies were designed to honor the zemis, seek blessings for crops, ensure successful hunts, and promote health and well-being in the community. These ceremonies could be held for specific purposes, such as harvest celebrations or healing rituals.

Batey Ceremonies (Ball Game Rituals)

One of the most important ritual spaces in Taíno culture was the batey, a ball court used for playing a ceremonial game called batus or ball game. The ball game held deep spiritual significance, as it was believed to be a way to honor the zemis and promote unity within the community.

The Game: Played with a rubber ball, the objective was to pass the ball through stone rings using only the hips, elbows, and knees, without letting it touch the ground. The game was often highly symbolic, representing the struggle between good and evil forces, or the balance of life and death.

Ceremonial Importance: The games were sometimes played as a way of communicating with the gods, asking for their favor or showing gratitude. Participants might also wear special clothing or paint their bodies with symbols to invoke divine protection or to symbolize their connection to the zemis.

Offerings: Before or after the game, offerings of food, tobacco, and other symbolic items might be made to the zemis as part of the ritual.

Areyto (Ceremonial Dance and Music)

Areyto was a major part of Taíno ceremonies, particularly during times of celebration or worship. It involved communal singing, dancing, and drumming, and it played an important role in passing down history, mythology, and traditions.

Purpose: The areyto was performed to honor the gods, celebrate victories, commemorate important events, and tell stories of the past. It was often performed in a circle or a line, with people chanting, clapping, and dancing in rhythmic unison.

Music and Instruments: The sounds of the areyto were produced using maracas, drums, and other percussion instruments. Hollowed logs were used as drums, and participants might sing in a specific cadence to invoke the spirits.

Spiritual Connection: The dance was not only a social activity but also an important spiritual act, as it helped maintain the balance between the physical and spiritual worlds. The dancers believed they were communicating with the zemis through their movements and songs.

Healing Ceremonies

The Taíno people placed great importance on physical and spiritual healing. The bohíque, or priest/healer, played a central role in these ceremonies. Bohíques were skilled in herbal medicine, rituals, and spiritual practices, and they acted as intermediaries between the human world and the spirits.

Healing Rituals: A bohíque would conduct ceremonies that included chanting, offerings, and the use of medicinal plants to heal physical ailments or ward off bad spirits. Healing ceremonies were often performed in sacred spaces, such as caves or other natural locations believed to be imbued with spiritual energy.

Herbs and Remedies: The bohíque would use medicinal plants like tobacco, cassava, and bitter herbs to treat illnesses or injuries. These plants were believed to have both physical and spiritual properties.

Spiritual Cleansing: Cleansing rituals, which might involve smoke from burning herbs, were used to purify individuals who were sick or suffering from spiritual imbalance.

Funeral and Ancestor Worship

The Taíno people believed in the continuity of life after death, with ancestors playing an active role in the lives of the living. Funerary ceremonies were conducted to honor the dead and maintain their spiritual connection with the living community.

Burial Practices: When a person died, they were often buried in a seated position, facing a specific direction. The Taíno believed the deceased would need to journey to the afterlife, and their burial site was thought to be a gateway to this journey.

Offerings to Ancestors: The Taíno would make offerings to the deceased, such as food, tobacco, and personal items. These offerings were meant to ensure that the ancestors had what they needed in the afterlife and would watch over the living.

3. Sacred Ritual Objects

Taíno ceremonies often involved the use of sacred objects that were believed to hold spiritual power.

Zemi Idols: Small stone or wooden carvings representing the gods and spirits. These idols were often placed in ritual spaces or held during ceremonies.

Duho: A ceremonial chair, often elaborately carved, used by the Cacique or important spiritual leaders during ceremonies. The duho was a symbol of authority and power.

Cemí Stones: Stones that were believed to house the spirits of the zemis. They were often placed in special shrines or used during rituals to communicate with the gods.

4. Role of the Bohíque (Priest)

The bohíque was the spiritual leader and healer of the Taíno community. This individual held immense respect and was considered a link between the human world and the spirit world.

Sacred Knowledge: Bohíques were deeply knowledgeable about herbal medicine, divination, and the rituals required to communicate with the zemis. They could predict weather patterns, diagnose illnesses, and guide the community in their spiritual and physical well-being.

Ceremonial Leadership: During ceremonies, the bohíque would guide the participants in chants, prayers, and offerings. They were also responsible for leading the areyto dances and playing important roles in the communal rituals.

Taíno ceremonies were a vital part of their culture, blending spirituality with daily life and connecting them to the natural world. While the full scope of their religious practices was deeply affected by the arrival of Europeans, many elements of Taíno spirituality continue to influence Caribbean cultures to this day, particularly in the form of rituals, music, and agricultural practices. Taíno Warriors

The Taíno warriors, or behique (shamans) and naborías (commoners), were integral to their society, and their roles were not just about combat but also about protecting their communities and maintaining order. Here are a few key aspects of the Taíno warriors:

Combat and Defense:

Taíno warriors fought with weapons made from natural materials. They used machetes, spears, and bows and arrows for defense and hunting.

They also used turtle shells and stone weapons. Their wooden shields were used to defend against attacks.

Bohio and Tribal Leadership:

The Taíno lived in villages called bohios, and each village had a leader called a Cacique. The Cacique was the supreme authority, responsible for the defense of the people, among other duties. Warriors were often directly under the command of the Cacique during times of war or conflict.

The Bohique, or spiritual leader, also had some influence over military decisions, as spiritual beliefs were intertwined with daily life.

Tactics and Organization:

The Taíno were skilled in guerrilla warfare and had a deep knowledge of the terrain. They used the dense forests, caves, and coastline to their advantage in ambush tactics.

They often attacked in small, highly mobile groups, utilizing stealth and surprise.

Religious and Ceremonial Role:

The warrior class also had a religious role. Warriors participated in ceremonies and rituals to gain favor from the gods for success in battle.

The Taíno believed in a range of deities (called Zemi), and the Caciques, as leaders, would often invoke these spirits for protection.

Resistance to Colonization:

When Europeans first arrived, the Taíno initially tried to resist Spanish colonization, led by warriors and Caciques like Hatuey (from Cuba) and Caonabo (from Hispaniola). Despite their best efforts, the Taíno were devastated by diseases, enslavement, and warfare.

Over time, many Taíno warriors either assimilated into the new colonial systems or were wiped out by European forces.

Cultural Symbolism:

In Taíno culture, warriors often wore distinct symbols to represent their status. For instance, they would paint their bodies with natural pigments, and wear jewelry made from shells and bones.

These symbols also had spiritual significance, as warriors were seen as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual worlds.

The warrior class in Taíno society was essential not only for defense but also in maintaining social order and cultural identity. Though the Taíno faced massive disruption due to European colonization, their influence and resilience remain an important part of Caribbean history and identity today.

You said:

Taino warriors in greater details

ChatGPT said:

The Taíno warriors played a crucial role in the complex social, cultural, and political structure of the Taíno people in the Caribbean. Their significance went beyond mere combat; they were symbols of strength, courage, and resilience. Let’s explore the Taíno warriors in greater detail, from their social roles and military strategies to their cultural practices and spiritual significance.

1. Social and Military Structure

The Taíno society was highly structured, with each community (or yucayeque) led by a Cacique (chief), supported by a Bohique (shaman or healer). The Cacique's role was not only political but also military, especially in times of conflict. The military hierarchy consisted of various roles, with warriors at the core.

Cacique: The chief and military leader. The Cacique was responsible for directing war efforts, organizing defense, and maintaining peace within the community. The Cacique often called upon his warriors in times of external threat.

Naborías: These were the commoners of Taíno society, often working as farmers, fishermen, and artisans, but they could also be called upon to fight in times of war. While not professional soldiers, they formed the backbone of the Taíno military forces.

Bohique: While primarily spiritual leaders, the Bohiques also played a role in military matters, particularly in advising the Cacique on divine will and making decisions based on religious beliefs. Their involvement in rituals was believed to protect warriors in battle.

2. Weapons and Warfare

Taíno warriors used a range of natural materials and techniques in combat, reflecting their deep knowledge of the environment and available resources.

Key Weapons:

Machetes (Macanas): The macana was a large, wooden club often reinforced with stone or shells. The Taíno crafted these weapons with sharp edges, making them effective for close combat and hacking. It was one of the primary weapons used by the warriors in battle.

Spears (Arco y Flecha): The Taíno also used spears, which were sharpened from wood or bone. They had long range and could be thrown in battle. In addition, the Taíno were skilled archers who used bow and arrows made from wood, fibers, and feathers.

Atlatl (Throwing Spear): An atlatl was a throwing weapon used to launch spears with greater force and range. It allowed the Taíno to strike their enemies from a distance, which was a significant advantage in battle.

Slings (Hondas): Another important weapon was the sling, made of fibers. The Taíno used it to hurl stones or small projectiles at enemies, much like ancient armies across the world.

Turtle Shell Shields: Taíno warriors used shields made from turtle shells for protection during battle. These shields were strong and light, and they effectively shielded the warriors from both arrows and melee attacks.

Tactics:

Ambush and Guerrilla Warfare: Taíno warriors were skilled in guerrilla warfare tactics, using the dense Caribbean forests, mountains, and caves to their advantage. They were adept at ambushing enemy forces and using hit-and-run tactics.

Surprise Attacks: The Taíno could strike unexpectedly, often launching attacks on unsuspecting groups or settlements. Their knowledge of the terrain allowed them to conceal their movements and gain the upper hand.

Naval Tactics: Taíno warriors were also skilled at naval warfare, as the Caribbean islands were surrounded by water. They used canoes (called canoas) made from hollowed-out logs to move swiftly across waterways, sometimes in coordinated attacks from the sea. These canoes could carry warriors and supplies.

3. Role of the Cacique and Bohique in Warfare

The Cacique had absolute control over military decisions. However, in times of war, it was common for the Cacique to consult with the Bohique (spiritual leader), as religious and spiritual guidance was considered vital for success in battle. The Bohique would often perform rituals, make offerings, and use religious objects to ensure the protection of the warriors and the success of the community.

Bohique's Role: The Bohique was responsible for invoking Zemi (spirits or gods) for support in battle. The Zemi were believed to guide the Taíno people in both everyday life and warfare. Warriors would sometimes carry amulets or tattoos representing the Zemi, believing that the spirits would offer them protection and strength.

Ceremonial Warfare: Warfare in Taíno culture wasn't just about fighting—it was also deeply ritualistic. Before battle, warriors often participated in religious ceremonies to ensure divine favor. Drumming, chanting, and dancing were common practices in these ceremonies.

4. Religious and Cultural Significance of Warriors

To the Taíno, the role of the warrior was not solely physical; it had significant spiritual dimensions. Warriors were considered protectors of their people, and their bravery in battle was seen as an offering to the gods.

Spiritual Symbolism:

Zemi: The Taíno believed in a pantheon of gods and deities known as Zemi. These gods were represented by various objects, such as stones, idols, or painted symbols. Some Zemi were associated with natural elements, such as the sun, moon, and sea, while others were linked to particular aspects of human life like war and fertility.

Tattooing and Body Art: Warriors would often wear tattoos or paint their bodies with symbolic markings before going into battle. These marks were believed to imbue the warriors with strength and spiritual protection.

Cohoba Ceremony: The Cohoba ceremony was an important ritual involving the inhalation of sacred tobacco or snuff through a pipe to communicate with the gods. Warriors often took part in these rituals before battles or significant events, as they were believed to receive visions or guidance from the spirits.

5. Warrior Class and Gender

Although the warrior class was predominantly male, there were instances where women also took part in military activities. Women played significant roles in society, often in leadership and spiritual functions, but certain women—especially those with high status—were trained as warriors and fought alongside men.

Dona Blanca and Anacaona: Some female Taíno leaders, such as Anacaona, the queen of Hispaniola, are notable for their resistance against Spanish forces. Anacaona attempted to lead her people in the face of Spanish colonization, and her leadership showcased the pivotal roles women played in Taíno society.

6. Resistance to Colonization

When the Spanish arrived, the Taíno warriors were among the first to resist. The most famous Taíno warrior leaders include Caonabo, Hatuey, and Anacaona. Despite their resilience, the Taíno warriors faced overwhelming odds due to superior Spanish weaponry, the introduction of European diseases, and the sheer number of invaders.

Hatuey: A Taíno Cacique from Cuba, Hatuey led a resistance against the Spanish during the early years of colonization. His efforts, while ultimately unsuccessful, made him a symbol of resistance.

Caonabo: The Taíno chief of Hispaniola, Caonabo was another figure who led the Taíno in resistance against Spanish forces. He was captured and taken to Spain, where he died.

Though the Taíno were ultimately devastated by European conquest, their culture, warrior spirit, and resistance continue to influence Caribbean identity to this day.

7. Decline of the Taíno Warrior Class

By the early 1500s, the Taíno warrior class was severely weakened due to several factors, including:

Diseases: Diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza decimated the Taíno population, weakening their ability to resist colonization.

Enslavement: Many Taíno were enslaved by the Spanish, and those who were not killed in battle or by disease were forced to work in the mines and on plantations.

Cultural Assimilation: The decline of the Taíno way of life and their absorption into colonial systems led to the disintegration of the traditional warrior class.

Despite these challenges, the Taíno's legacy lives on in the Caribbean, where their culture, language, and resilience continue to shape modern societies.

Taíno warriors were not only military figures but also cultural and spiritual symbols for their people. Their legacy is an enduring part of Caribbean history and continues to inspire those who trace their heritage back to the original inhabitants of the Caribbean islands.